A Place For My Stuff

And Say Children: What Does it All Mean?

During the 1980s, my maternal grandparents lived in a three-story stone home less than an hour’s drive from downtown Brussels. I visited their home at least a half-dozen times as a child. When I was sixteen, I stayed in the attic bedroom, formerly my uncle Herve’s domain. The walls were slanted on a 45-degree angle, a window on one side, which made me feel as if I were sequestered at the top of a castle.

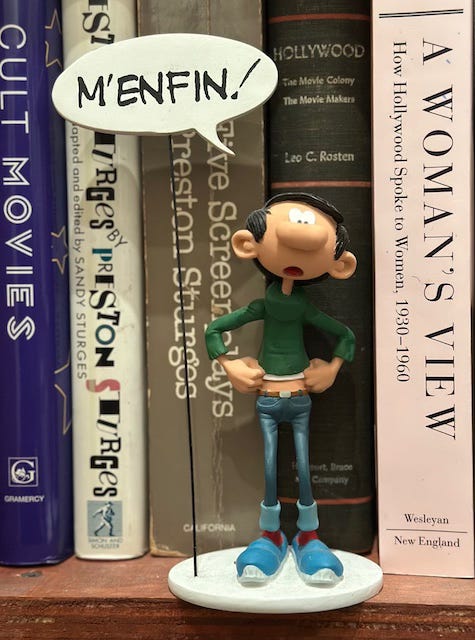

An old radio in the corner of the room picked up BBC 4 and I relished hearing my native tongue. Dozens of hard-backed comic books (Bandes dessinées) lined the floor next to the bed, all in excellent condition, with Herve’s name hand-written on the first page.

The attic was separated in two—one part the bedroom, the other a storage space, where I snooped through old bureaus and dressers, standing lamps and other dusty remnants of my grandparents’ past life in Africa. Once, I found a French porno magazine in one of those drawers which encouraged me to feverishly hunt in vain for more.

Most of the stuff that appealed to me was in a form of disrepair—a broken 35mm camera, the 8mm projector in need of a bulb—and the one perfect item, a smooth, delicate wooden cigarette case, wasn’t mine to have.

In the 1950s, my grandparents lived in Bukavu, a town in the eastern part of the Congo, near the Rwandan border. My mother was three years old when my grandfather brought his young family to Africa in 1947, where he ran the garage for a Renault dealership. Three days before the Congolese Independence in late June 1960, Mom and her sister were put on a DC-3 at the local air strip with two of their friends and sent back to Belgium for what they thought was summer vacation.

They carried a knapsack and some clothes and never went back. Their pets, their friends, their life, gone.

My grandmother—Bonne maman—joined them in Belgium a few months later and for the next few years, my grandfather—Bon papa—tried to salvage his business and a life that had already vanished. He lost whatever money he’d made and returned to Belgium as broke as he’d been thirteen years earlier.

By the end of the decade, he returned to what was then called Zaire, and lived in Kinshasa, on the other side of the country from Bukavu, with my grandmother and my mom’s two youngest siblings. As a child, I didn’t know anything about the politics of Colonialization; my grandparents were from a generation that took European superiority as a given, not an outrageous entitlement.

They didn’t question it, it was assumed, and came back with mementos rather than riches—a framed painting on goat skin, a lump of volcanic ash, a malachite ashtray, symbolic of the mineral riches ravaged by outside forces, from Belgian and beyond.

During their second stint in Africa, my mother had landed in New York and married into a Jewish family. My father’s parents arrived in New York in 1912 and 1916, from Russia and Poland respectively, making my father a first generation American. My grandparents didn’t carry many family heirlooms from the Old World; apart from some old photographs, I can’t think of anything they kept from Europe.

They were Americans and their stuff is from their American life. For New Yorkers, the place for your proverbial stuff, beyond the confines of your apartment, is generally the dank, ill-lit, and slightly treacherous storage facility located in the building’s basement.

After my father’s parents died in the late ’80s, he kept a bunch of their stuff, as did his sister and the rest of us. You don’t just throw away books. You find new homes for them. I still have at least a dozen from my grandfather’s collection. Correspondence too, photographs and miscellanea such as articles my grandfather wrote for the Brooklyn Eagle in the 1930s or copies of the family income taxes from the early ’50s.

When my father died in 2007, I took on a good deal of his stuff and happily parted with the rest. My brother waded through Dad’s prodigious collections of tools. In addition to being a man of words, my father was a handy guy who loved hardware store tools like some dudes like cars or record stores.

Along the way, I’ve held on to things like I’m Steve Martin at the end of The Jerk, unable to leave without just taking one last item. When Richard Ben Cramer passed away and his wife offered me his sports library, I said, “Of course,” and to my wife I said, “We’ll find room.” Ditto when Ray Robinson’s children cleared out his apartment ready to toss his unwanted collection of sports books.

When Emily and I moved out of the Bronx five years ago—where I had two storage units—one of the movers told me they’d moved small town libraries with fewer books. And that’s before the records, and the magazines.

Feel the walls closing in on you?

Actually, through the decades, I’ve regularly pruned my loot and have parted with thousands of books and records. Having watched my parents move homes a few years ago when they got rid of a ton of stuff, I’m conscious of the significance of it all. Who cares about my stuff other than me? Never mind thinking about who would deal with it if I dropped dead tomorrow?

I visited Gay Talese’s storied townhouse a few years ago and strolled through the ground floor living room and sitting room, shelves lined with hardcover copies, most first editions, from Talese’s friends and peers—David Halberstam, Robert Stone, Norman Mailer. In the front room, there was an impressive display of Talese’s books, all sorts of editions and translations. It was something to admire but I couldn’t shake a sense of impermanence. In Gay’s case, there will be plenty of interest in his stuff—his downstairs work study is an archivist’s playground. But still, once he’s gone, the place for his stuff will change.

And when the place changes, so, in a way, does the stuff.

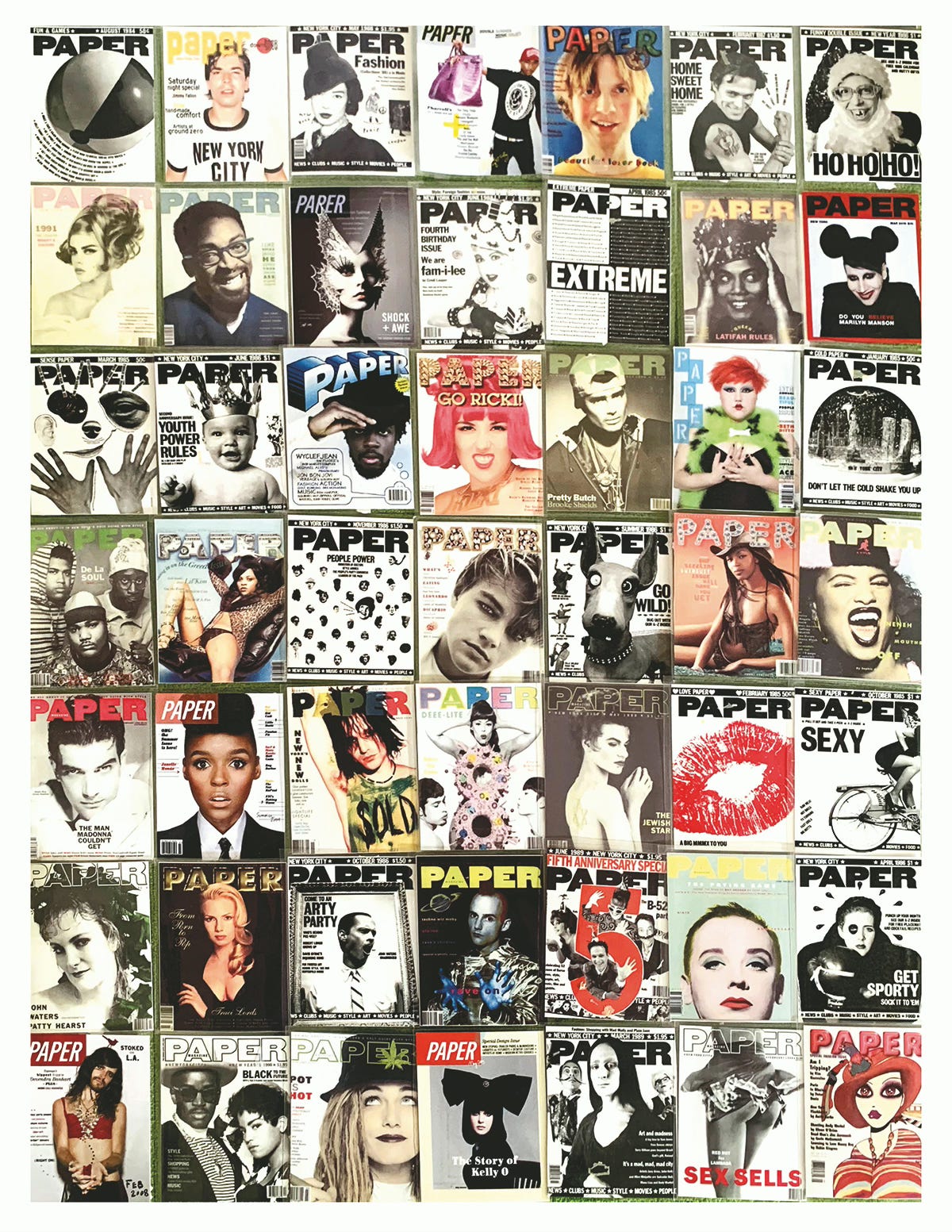

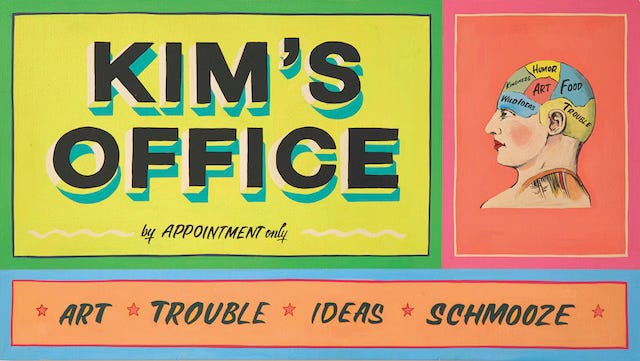

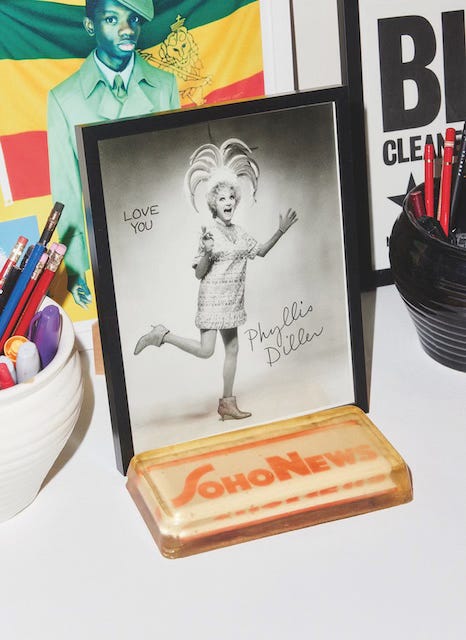

Two memoirs that recently arrived that I have added to my stuff are, STUFF: A New York Life of Cultural Chaos by Kim Hastreiter and Comedy Nerd by Judd Apatow. A doyenne of the downtown arts scene, Hastreiter was the editor of Paper magazine, and her memoir is a loving place for her most excellent stuff.

“I am a fanatical collector and curator of ‘stuff,’ ” writes Hastreiter. “Mostly stuff that I think is amazing, important, tells a good story, or just grabs my heart.” Hastreiter calls herself a snob; she has taste discretion and just the most terrific collections— from skateboards to soup ladles to artwork by Keith Haring and Jean-Michel Basquiat. Housed in Hastreiter’s boss Greenwich Village apartment, they now live with us in this beautifully realized volume.

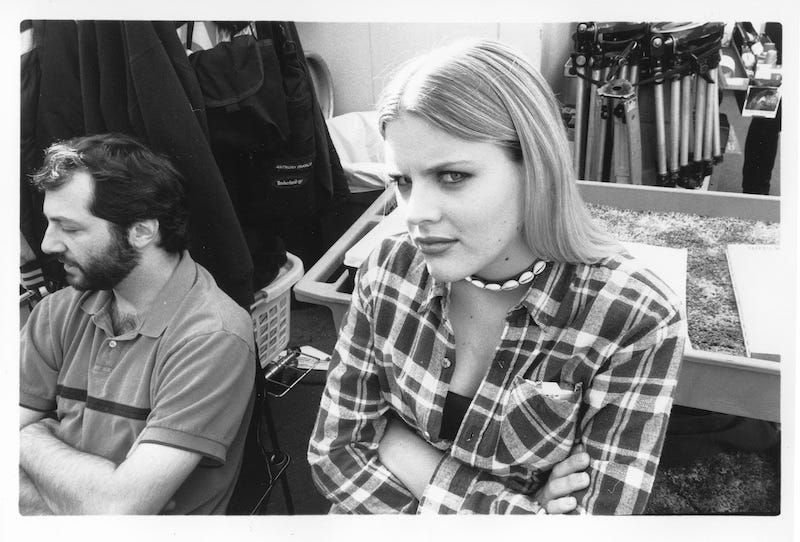

Judd Apatow has also lived an enviable life and I pored through this visual memoir—featuring lots of writing—appreciating just how much he’s accomplished. Apatow’s a hoarder by nature. As a kid he wrote letters to celebrities for their autographs, which they sent and he dutifully preserved.

Comedy Nerd, which I reviewed in brief for The Wall Street Journal last month, serves as a kind of career scrapbook, and I like how Apatow includes magazine articles written about him—reprinting the original magazine layouts in their entirety. The book documents seemingly every project Apatow has ever done and not done—the cool ideas and TV pilots that didn’t take off.

Which brings us back to Garry Shandling, who, when asked by Esquire in 2003 what he’d learned about life, replied in part: “Impermanence, impermanence, impermanence.”

Our stuff matters, whether we cling, covet, or discard it. We cling because of impermanence. Stuff disappears. So do our stories. What’s meaningful is how they put us into relation with others. I’m surrounded by my stuff but can’t shake Shandling’s impermanence mantra.

I think both sets of grandparents all the time. I have the wooden tongs Bon papa used for pots of cornichons; hardbound volumes of Shakespeare, de Maupassant, and Kipling, the only English books they owned; and Bonne maman’s salt box. It’s a modest terra cotta box, right out of a Morandi still life. I don’t know the story behind it or how long Bonne maman had it in her kitchen. I do know that she used it every day when she cooked, as I’ve used it every time I cook since she died thirty years ago.

At the end of his book, Apatow writes:

“I have always been a hoarder, and I have hope that completing this project will allow me to finally throw about a hundred boxes of stuff that I always though essential in case I might do something like this one day. What do I think when I look through the book? First, I think, man, that is a lot of stuff. What the hell is wrong with you? How insecure and needy and broken are you that the only way to deal with it was to create this mountain of work? Was it a healthy expression of your creativity, or, as Garry used to say, the essence of your soul? Or was it a desperate cry for help from a person that never feels whole, whose pain and trauma never eases, and who needs to numb himself with busyness and accomplishment?”

What, if anything, does our stuff say about us? I can tell you why I have almost every book I own, and some are completely random. I’ve kept books for sentimental reasons that have nothing to do with their content. I lugged around a copy of Moss Hart’s Act One for two decades before I made it past the first page.

When I did, I understood why Frank Rich called it “the greatest showbiz book ever written.” Hart’s depiction of the playwriting process is riveting—nonpareil—as is his unrelentingly furious account of growing up poor. My father recommended I read it. I can see it on the shelf, a book of his time, not mine.

I don’t know what’s happened to my copy, only that I bought a used hardcover for less than five bucks at the Strand in 1987 when I was sixteen. I finally read it over the course of week in my early 40s—on the 1 train at rush hour, on the living room couch with Emily and our two cats as they napped—and now it’s gone.

[Photos appear with permission. From Stuff: A New York Life of Cultural Chaos by Kim Hastreiter published by Damiani; and Comedy Nerd by Judd Apatow published by Penguin Random House.]

Stunning reflection on objects as memory anchors. The shift from Bon papa's cornichon tongs to Shandling's impermanence hits diferent when you realize collecting isn't about owning, its about refusing to forget. I've been wrestling with this in my own space latley, and the bit about how 'when the place changes, the stuff changes' kinda nails why we hold onto things long after their utility fades.

Loved it, as ever. You have Richard Ben Cramer's sports library?!? Epic. In my life, the undisputed King of Interesting Stuff will always be our mutual friend, the late Bill Zehme. His former loft was, and his current storage space is, crammed with it.