We’re in the mid-1980s, 1987 to be exact. I’m a Gen X kid who loves both movies and sports. With Reagan in the White House, and the mood in the air distinctly conservative, it’s no wonder that baseball movies enjoyed a brief run of popularity.

You feel it watching Robert Redford in Barry Levinson’s glossy 1984 adaptation of Bernard Malamud’s admired novel, The Natural, a movie that turned a hard- luck ending into a triumphant moment of slow motion winning.

Then in ’88 and ’89 came Bull Durham, Eight Men Out, Field of Dreams, and Major League.

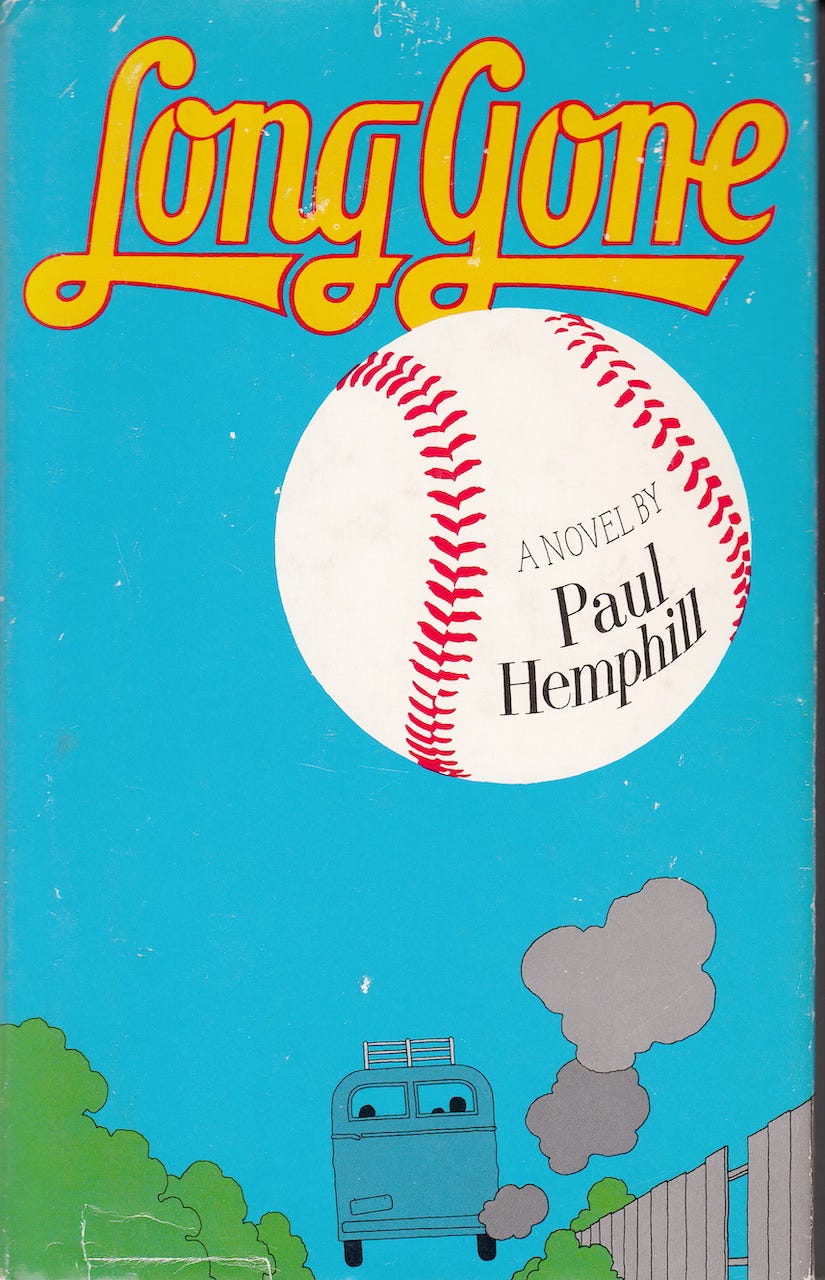

The sleeper in the mix is Long Gone, released in ’87, which bypassed theaters and went straight to HBO, at the time a graveyard for features. On the other hand, it was a well-attended graveyard for Gen X kids, and Long Gone quickly became regular viewing.

The first thing it did was introduce me to Hank Williams, whose music I hadn’t heard growing up in New York. I’d already been opened up to the pleasures of country music from the yodeling theme from Raising Arizona, which came out in March of that year. That yodeling wormed into my head and wouldn’t leave.

Couple of months later, this baseball movie about the low minor leagues in the South during the ’50s—like Bull Durham, Long Gone is best as a sex comedy—is named after a lyric in a Hank Williams song.

Consider me changed.

Jack Nicholson reportedly had interest in playing the lead. Dustin Hoffman too, odd as that sounds. But William L. Peterson — in a welcome departure from the heavy roles he played at the time in To Live and Die in L.A. and Manhunter — is loose, with the same, over-the-hill spark that made Paul Newman such a beast in Slap Shot. Virginia Madsen, as the moral conscious of the movie, swipes the movie from everybody, though; she’s hilarious, smart, and smoking hot.

And in what proved to be an inspired piece of casting, Henry Gibson and Teller play the sniveling father and son ownership team of a low-minor league team (Preston Struges would have approved.)

Long Gone is saddled by some clunky plot turns, including a dramatic big game at the end—which Bull Durham wisely avoided. At the same time, there’s no lofty speech-making either; safe to say, Stud Cantrell never came close to a Susan Sontag book let alone reading one.

Cut to 2007, two decades after it originally aired. I’m running a Yankee-based baseball blog, Bronx Banter, immersed in baseball culture, when I get to thinking about Long Gone again. It wasn’t available anywhere, though you could get old videotapes on ebay—these days it’s not streaming but you can find it on You Tube.

I went out and bought the funny 1979 novel by Paul Hemphill and loved it as much as the movie. I’m a sucker for terse books, especially novels, and Long Gone weighs in at a tidy 213 pages.

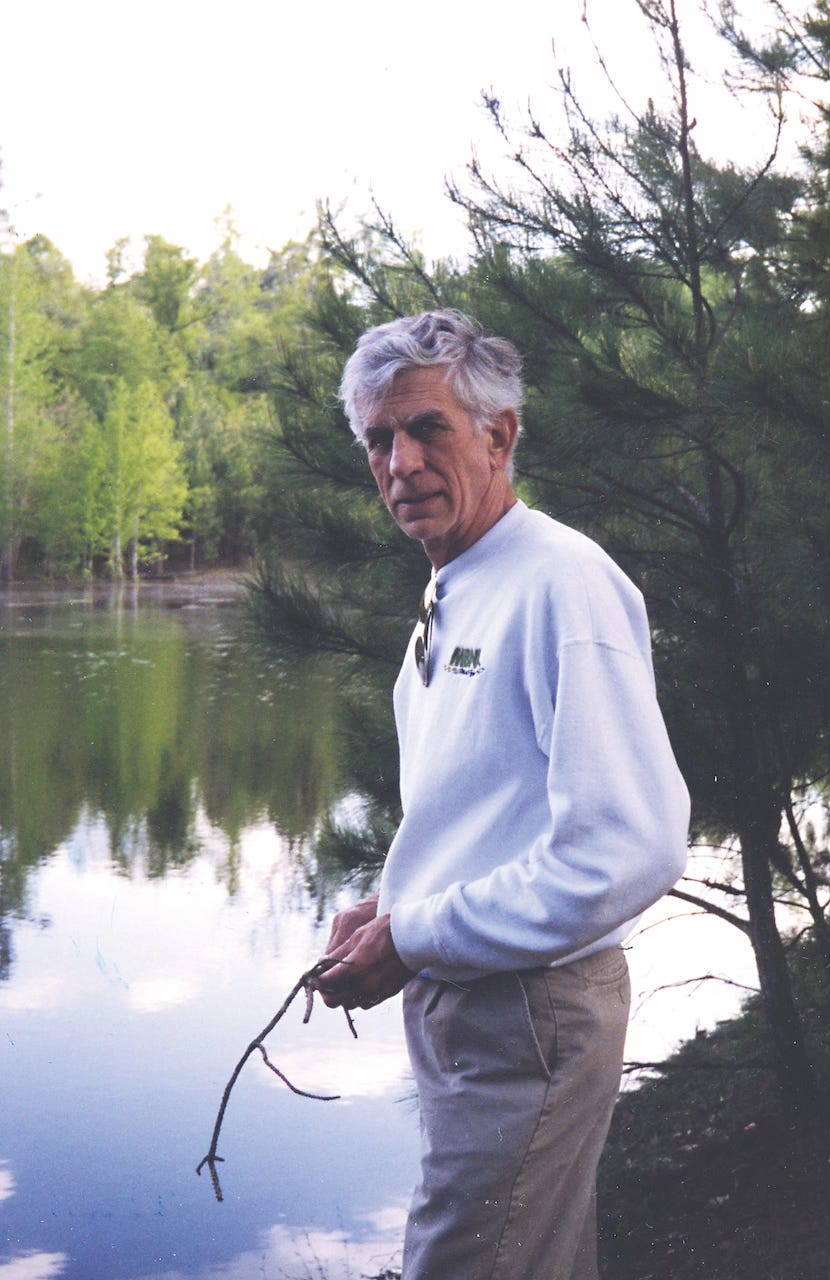

I wanted to know more about Hemphill, so I bought his memoir, Leaving Birmingham, then tracked him down. We exchanged emails, and I gave him a call. He was already sick with the cancer that would kill him, his voice scratchy though he seemed happy to talk, especially about Long Gone.

Turns out it’s based, in part, on his life. Hemphill is the Jamie Weeks character, the young second baseman, though Hemphill’s professional career didn’t last but a couple of weeks. Born and raised in Alabama, the son of a trucker, Hemphill’s only plan growing up was to be a professional ballplayer.

With that quickly off the table, he enrolled at Alabama Polytechnic Institute—which changed its name to Auburn University in 1960. That’s where Hemphill joined the school paper and embarked on a career as a sportswriter; he covered the basketball team the year they won a national championship. After interning at the Atlanta Constitution (Journal and Constitution were separate papers then; they combined their newsrooms in 1982, then fully merged in 2001) he began his career at the Birmingham News.

There was a stop in Augusta, then Tampa, at a time when $10 extra dollars a week more would get you to move to another state.

Hemphill returned to Georgia to write a general interest column for the Atlanta Times, an arch-conservative paper. He was there less than a year before moving to the Atlanta Journal, an afternoon paper, a working man’s paper, where for the next half dozen years—he was at the Journal from 1965 until 1970—Hemphill delivered six, 1,000 word columns a week.

Six columns a week!

“He was the kind of general newspaper columnist that hardly exists anymore,” Roy Blount Jr., who worked with Mr. Hemphill at the Journal, later told the New York Times. “He’d go out and do things and talk to people...He wasn’t a talking head; he was walking ears, or listening legs.”

They called Hemphill a southern Jimmy Breslin and the comparison stuck. Since Hemphill greatly admired Breslin, he took it as a compliment. Hemphill didn’t imitate Breslin’s style or attitude—Hemphill was a warmer presence by far, his prose clean, not spare, using an economy of words to convey the story—but he wrote about real people and had a feel for them and the lives they lived.

Hemphill had compassion and understanding of people with whom he didn’t agree—and this stems from a complicated but loving relationship to his old school father who harbored old school bigotry.

“All I know is truckers and hillbilly singers, if you insist on calling them hillbillies, and people who sell plastic Jesuses out on the highway. I don’t understand Grace Kelly. I live in the South because I’ve got a sense of place here.”

In 1968, Hemphill got a much-needed reprieve from the pressure of his column when he attended Harvard on a Neiman Fellowship (he was there for the 1968 -69 academic year). He felt completely out of place in northeast academic and literary circles, yet he joined the ranks of white southern male writers such as James Dickey, Barry Hannah, Willie Morris, Marshall Frady, Larry L. King—the Pork Chop Conspiracy, as it were—that caught the attention of the literary world.

As Hemphill later recalled: “I get a headache before I even get to the hotel every time I go to New York. I live here [in the South] because it is the only place I understand. I’m too old [37, then] to start learning a new place all over again. I went to Philadelphia last month to interview about a newspaper columnist’s job, and I wondered why I had even gone up there in the first place … All I know is truckers and hillbilly singers, if you insist on calling them hillbillies, and people who sell plastic Jesuses out on the highway. I don’t understand Grace Kelly. I live in the South because I’ve got a sense of place here.”

But it wasn’t too long after his time at Harvard that Hemphill realized something had to change. So he quit. “For reporters—even fledgling ones,” wrote his pal Steve Oney, “the move made him a legend.”

Hemphill’s first—and arguably best, book, and certainly the most financially successful, was the best-selling The Nashville Sound, which offers an inside look at the country music mecca in its heyday. It quickly became an indispensable volume.

In some ways, Hemphill could have leaned into the role as the official scribe of country music, could have just coasted on that alone, though it wasn’t his temperament. He resisted being pigeon-holed and while he later wrote a biography of Hank Williams, never was known as a country music writer or music writer.

There were more books, about a variety of things including NASCAR. He was especially fond of Leaving Birmingham and The Ballad of Little River. In the 1970s, Hemphill freelanced for magazines including Life, the New York Times Magazine, and The Atlantic. He was a regular presence in Sport.

Then came a divorce, and three kids to consider. Booze got in the way, too.

Here’s more from Oney, in a wonderful tribute he wrote about Hemphill for the Columbia Journalism Review, about Hemphill by the end of the decade:

The Good Old Boys, a collection of his magazine articles, had been published to superb reviews, but he was teaching at a small college in Florida, and his work was going slowly if at all. He was bogged down in a novel about life in the lowest rungs of minor-league baseball. He was falling behind on a biography of George Wallace for which he was under contract. Then there was the drinking. Too many of his letters began like this: “It is 11 a.m. and I am on my fourth Bloody Mary while Hemphill’s Famous Homemade Vegetable Soup boils on the late WW-II stove. I swear I am going to write on Wallace before I have to be somewhere at 3 p.m.”

“By the late seventies, following an aborted gig as a columnist for The San Francisco Examiner, Paul was back in Atlanta, where I had landed a job on the Journal & Constitution Sunday Magazine. We convened regularly at Manuel’s Tavern, the city’s Democratic Party watering hole. Delighted as I was to see Paul, I no longer idolized him. I had grown weary of his tendency to talk about the same subjects—his father, the bigotry of Birmingham, Johnny Cash, and the still-unfinished baseball novel—and I chafed at his lack of curiosity about life outside the South.

…“A sense of place” was another of Paul’s big phrases, and he invoked it like a credo.

This is revealed in Hemphill’s poignant, plain-spoken essay about his father, “Me and My Old Man,”—a meditation on bigotry, generational barriers, acceptance and going your own way. It’s worth your time and you can find it on my site, The Stacks Reader—a site devoted to reprinting classic journalism, mostly from the pre-digital era.

Maybe it’s because Hemphill was my father’s age, and like Gene Hackman and Paul Newman on the screen, you saw this generation of men, rooted in very traditional, hard guy versions of masculinity, trying to open themselves up to a different way of being, one of much deeper vulnerability.

The Stacks Reader is also where you’ll find a few of the pieces that we’ve got in store for you here. Collected in Hemphill’s 1981 anthology, Too Old to Cry, they are three columns and one longer essay.

The columns—“Mr. Ham’s Overcoat,” “Hitching,” and “The Telegram” are shorter, and great examples of the kind of storytelling Hemphill delivered on deadline; they are followed by a longer piece, “Quitting the Paper,” Hemphill’s farewell as well as his ode to his days working in newspapers. It’s a doozy of a goodbye.

Hemphill’s stories are read by my dear friend Malcolm Jones. MJ was the longtime book editor at the Daily Beast, Newsweek, and before that, the St. Petersburg Times, which, like many regional newspapers in the 1980s, had a bitching arts section. Malcolm is also the author of one of my favorite memoirs, Little Boy Blues—and if you’ve never read it, do yourself a favor, track it down, or if you spot it in a used bookstore, pick it up—it’s a real pleasure.

And with that, let’s dig into a glimpse of Hemphill’s America.

[Photo Credit: “31 Cent Gasoline Sign, near Greensboro, Alabama” by William Christenberry (1964), via The Art Institute of Chicago; portrait of Hemphill by Susan Percy]

Share this post