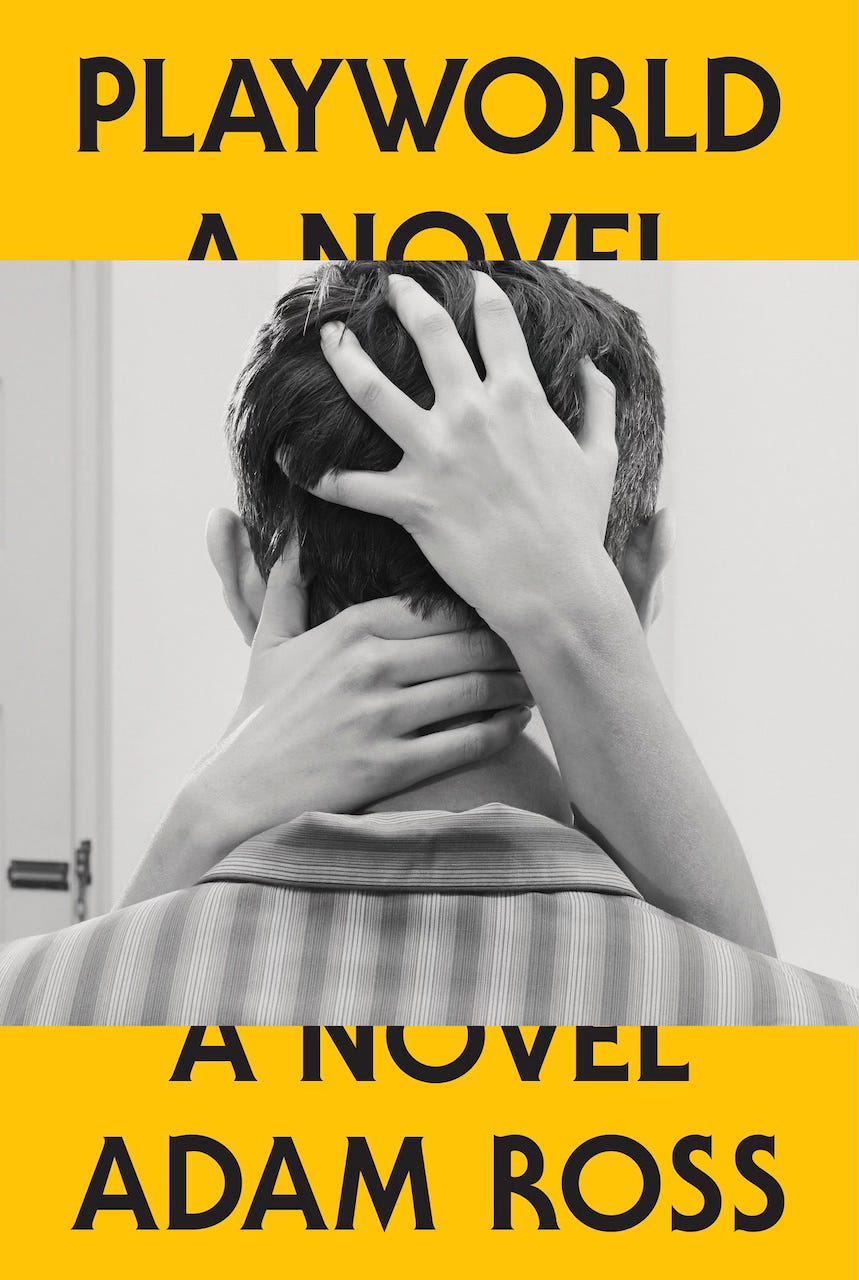

“Adults, I think now, were the ocean in which I swam.”— Adam Ross from Playworld.

Earlier this year, Washington Post book critic Ron Charles concluded an enthusiastic review of Adam Ross’s novel Playworld with: “Starting off 2025 with a novel this terrific gives me hope for the whole year.”

That was more than enough for me.

Months later, having read the book twice—and listened to it once on Audible—I’m still under its spell. Playworld hit me with the force of something I didn’t know I needed but did—satisfied cravings I didn’t recognize until reawakened.

The novel tells the story of Griffin Hurt, a 14-year-old boy growing up on the Upper West Side of Manhattan in the year 1980-’81, who has an affair with a 36-year-old mother of two. Naomi Shah is a friend of the family who shares the same therapist, Elliott Barr—the Hurt family shrink, who is also best friend to Griffin’s father, Sheldon. Because, of course he is.

Griffin is also predated upon by his wrestling coach, a mentor and looming figure in the book’s first half. We move with the kid as he juggles life as a high school student and working actor. He’s got outsized responsibilities—his paycheck makes up for his parents’ financial shortcomings—but he always seems to be in trouble — “in trouble” as a state of being, a disappointment to everyone around him, teachers, co-workers, classmates.

Griffin doesn’t tell the therapist about Naomi or coach Keppleman. He’s a good enough actor—admired professionally for his naturalism—to feign his way through sessions. He’s aware of his inability to truly express himself. The disassociation is overwhelming; Griffin blames himself for putting his shrink to sleep every week.

One day, in a moment of candor, he blurts out, “It’s like I’m a mute!”

Elliott awakens and tells Griffin an involved story about the famous acting brothers, Edwin and John Wilkes Boothe. It’s a tale with a moral—the quest for love and how trauma tethers people together, defines them.

Griffin notes Elliott’s actorly qualities as he speaks but the older man isn’t just a ham or a blowhard, and he notices more than Griffin suspects:

“Back in the office you said you felt like you were speechless,” he tells the Griffin. “That you had things you saw but struggled to communicate. Those are the two most heartfelt things you’ve ever shared with me. So maybe that’s what you’ve been put on the earth for. To come up with a language for your life.”

Griffin has no idea what he’s talking about, but Ross does, and in this compassionate, funny, and alive novel, he gives language to a young man’s life. It’s a subset of literary fiction my friend, novelist Rob Cohen, calls the “screwed-up young man at loose ends” that you don’t see much anymore (and that’s fine, it’s made room for more stories about screwed up young women at loose ends.)

Without sentimentality or nostalgia, Playworld is an evocation of a place and time that feels less like an interrogation and more like a love letter.

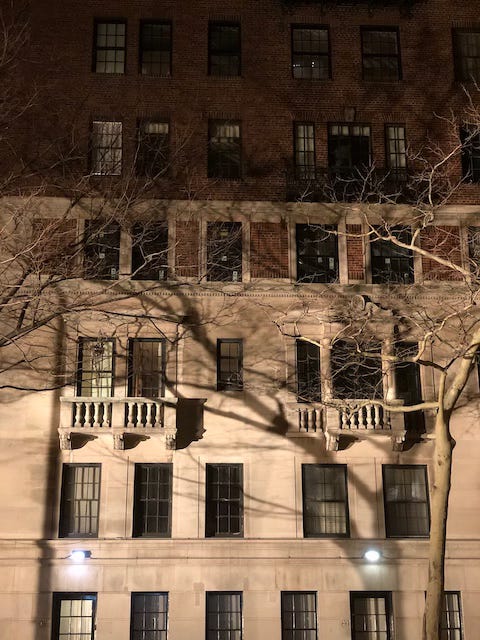

I grew up in the same neighborhood and though by 1980-’81 we’d moved north to Westchester, my father’s family remained, and we visited my grandparents, who lived across the street from the Hayden Planetarium and the Museum of Natural History, weekly. It was also the final year of my parents’ fifteen-year marriage.

Griffin’s story isn’t mine exactly—and thank goodness, if it were more on the nose I might have not been able to bear it—but it sure is familiar.

Four years my senior, Griffin is a guy I recognize, the kid from the apartment down the hall, yanking the chord first on a crosstown bus, or playing video games, quarters stacked high, at the 52nd street arcade on Broadway. Part of what made guys like that cool was their gait, the way they held themselves with a certain battered poise.

One of the many pleasures of Ross’s novel—a book unafraid to offer pleasure—is this sense of recognition. As a reader looking for my remembered reality in these pages I was reminded of the selectivity of city life. Everyone has their own, often isolated, experience. How fucked up is it in your home? How are you making it? It’s this people-watching lure that gives Ross’s novel such a familiar ache.

“You could never exhaust the totality of this city any more than you could the knowledge of another person, or yourself.”

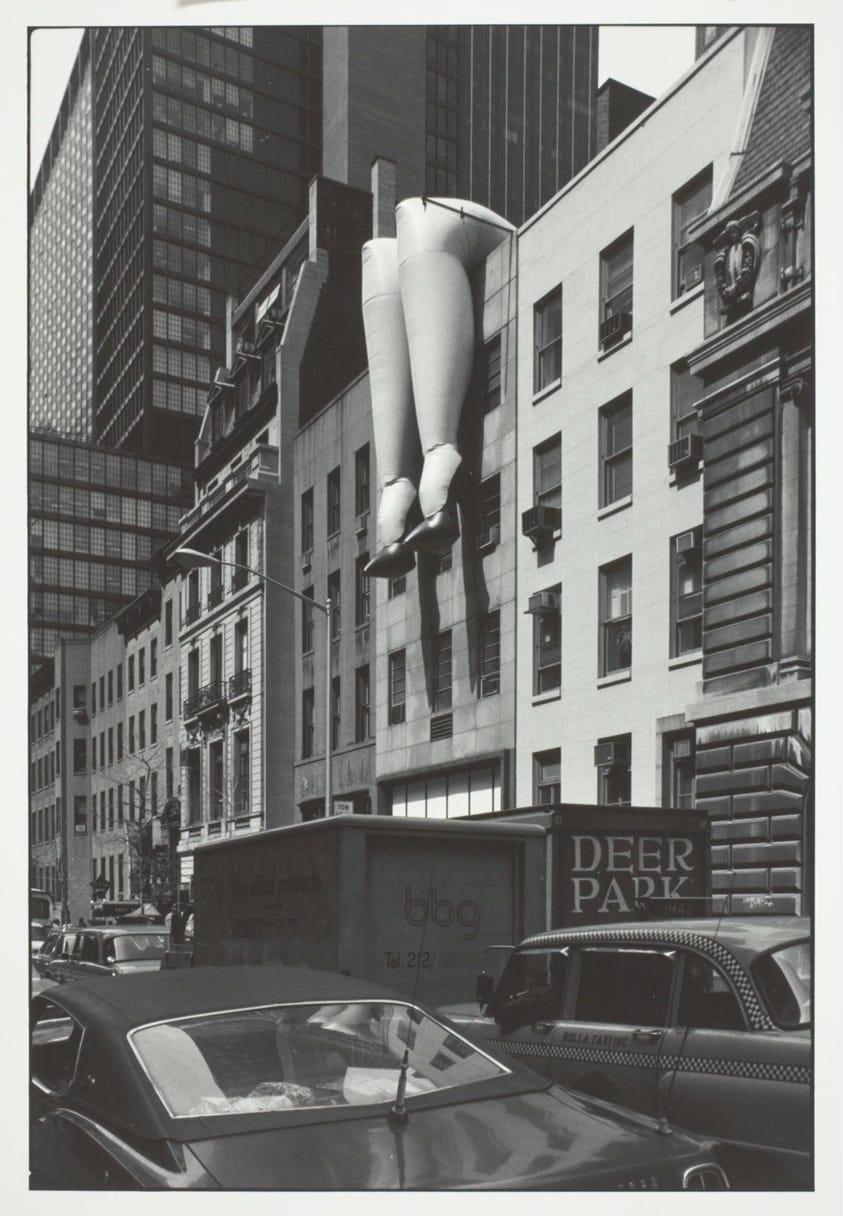

Griffin is the son of Sheldon, a middling stage actor who supports his family giving voice lessons and narrating TV and radio ads, and Lily, a former ballerina who teaches Pilates and is working on a master’s in American literature.

Griffin’s TV gig pays for his prep school where he devotes his attention to wrestling, at which he’s more earnest than good. His brother Oren, two years younger, also wrestles, and while they share the sport in common, they are otherwise not alike at all. Oren is the sly, smart-ass younger brother, who nurses his hurt behind a quick tongue.

When Shel gifts his boys new Stetson cowboy hats, Oren, who like Griffin, inherited his father’s fear of not being in the know, asks if he bought the hats himself—or if he got them as schwag for doing a commercial? Irritated, Shel snaps—what’s the difference? “That,” Oren says imitating Yoda— “is why you fail.”

Shel, who recites taglines from commercials throughout the novel, likely didn’t get The Empire Strikes Back reference—the movie came out the previous summer—but in this book every period detail is precise. Ross is gifted with an ear for dialogue, the rhythm of conversation, and he delights in a character’s ability to deliver a line. Perhaps these are byproducts of Ross having been a child actor himself, who like Griffin, “found his greatest subject to be adults.”

Griffin is at the mercy of these loving but hopelessly self-absorbed parents and exposed to the unforgiving meanness of the grown-up world. Everyone in the Hurt family is reeling from a family trauma that occurred several years earlier, each in their own private way, and one of the central tensions in Playworld is about how—or if—they’ll remain together.

Ross shifts into a slower more discursive gear in the middle sections of the book, permitting Griffin a childhood—the predatory forces in his life temporarily at bay—and Ross luxuriates in the freedom of adolescence.

This is a big novel, 502 pages, with the propulsion—and lulls—of a baseball game not a wrestling tournament, though the evocation of high school wrestling is one of the book’s crowning achievements. The John Irving comparison is inevitable—The World According to Garp makes a flash appearance when Griffin goes to the library looking for books on wrestling; otherwise, nothing about Playworld reminded me of Irving. While Ross’s world has a cinematic feel, its virtues are novelistic.

In interviews, Ross cites Saul Bellow’s expansive 1953 novel, The Adventures of Augie March as a model and inspiration; and there’s the ghost of Philip Roth too, without the burden of Roth’s autobiographical adobo.

The story is narrated by Griffin—not 14-year-old Griffin but an older one, looking back. The secret sauce, what really binds the narrative spell throughout, is how the older Griffin occasionally pauses, draws back, and comments on his younger self.

We’re not invited into a Holden Caulfield-conspiratorial relationship with Griffin; the older narrative voice comes in to explicate certain moments that are spiky, like when Griffin’s friends get revenge on a classmate by getting him shitfaced and then putting him on a subway to Harlem, which at the time, for a drunk prep school white kid, meant the worst kind of trouble.

Whether prompted by an editor or his own conscience to clarify the sensibility of the moment, Ross handles the task by taking us out of time, to New York and Griffin’s life decades later, with such deftness you don’t feel annoyed by the digression but grateful.

The older voice rarely comments directly on characters, his feelings on characters, or his feelings at all. The beauty of the older self comes through in the telling, rarely in the direct reflection as it does in, say, William Maxwell’s So Long See You Tomorrow.

Ross wants us to feel the pace of the city—the momentary clarity that comes when you lock eyes with someone as you pass each other in a whoosh. The heartbreaking serendipity:

“There must have been a spell cast upon it from before when this land was Arcadia, was Manahatta, and it is this: you can take two people, place them within shouting distance of each other, set them on their way, and in their lifetimes, they might never cross paths again. Even if it became their most fervent wish …”

Some of my favorite scenes in the novel occur outside of New York—in Florida, Washington D.C. and Long Island. Then too, you feel the city’s magnetic pull like when the family visit’s Lily’s parents in rural Virginia. Reading this about Shel—he could be my father or any number of relatives:

“Three days in and he was going out of his mind. So far as I could tell, his discontent was a function of his simply being out of New York. Robbed of its noise and bustle, he responded with an ever-increasing antsiness. As if by leaving Manhattan, Manhattan, in his absence, threated to disappear, and he must go back to it in order to preserve its existence.”

Has a truer statement ever been made of the New Yorker sensibility? Okay, how about this: “You could never exhaust the totality of this city any more than you could the knowledge of another person, or yourself.”

The chapter titles are a Gen Xer’s shorthand: “Dungeons & Dragons;” “There Is No Try,” for The Empire Strikes Back; “The Agony of Defeat” from ABC’s Wide World of Sports intro; “Double Fantasy,” of course referring to the killing of John Lennon.

Shelly Duvall, Jill Clayburgh and Muhammad Ali appear as themselves; the director, Alan Hornbeam, a riff on Woody Allen—if you mix in a little Kubrick, Mike Nichols and Terrance Mallick—is invented. So is Ellyse Baxter, who plays Griffin’s TV mom, the name a riff on Elyse Keaton, Meredith Baxter’s character on Family Ties—which had yet to air (there’s a sleight of hand reference to Elliott Gould, too).

And an even bigger Easter Egg in the “Lennon Shot” chapter, but even if you don’t get it—and I didn’t until someone pointed it out—the scene still works. Ross’s cleverness never gets in the way of the story.

I’m a sucker for show business and enjoyed the scenes on sound stages, movie sets and Broadway theaters. The stuff with the therapist is far from rote and Elliott delivers a lot of useful information to the kid—“Never mistake your own perceptiveness for self-awareness because one is an entirely different mode of knowledge than the other.”

I especially loved Griffin’s blue-balled naiveté, his yearning for a girlfriend, chasing after a number of alluring young women, and his affair with Naomi Shah. Yeah, I dug all the parts about sex, most humbling of all, Griffin’s sheer ignorance of his own sexuality and body.

I wasn’t prepared for the affection and love between Griffin and Oren despite the usual brotherly rivalry. The few scenes when they go at each other, I found almost too painful to read—and when I listened to Ross’s narration of the book, I fast-forwarded through their scuffle in Captiva, Florida, where a physical confrontation goes too far, the brothers now old enough to do damage.

“…Because our lives were so atomized, because we lived so unattended, because we were already so strangely private, access to each other’s inner lives did not come naturally.”

Or when Oren, bereft after he watches Griffin get brutally slammed during a tournament, cannot console him because he’s not allowed to fraternize with the opposition:

“I’m sorry I couldn’t help you,” he said, and was so distraught he excused himself and went to our room. There were times, as now, when Oren acted as if he’d failed me in some far more essential manner than the circumstance, when half the time I felt like I’d failed him, and this mystery made the gulf between us seem even more unbridgeable than the fact that we no longer spent our days at school together.

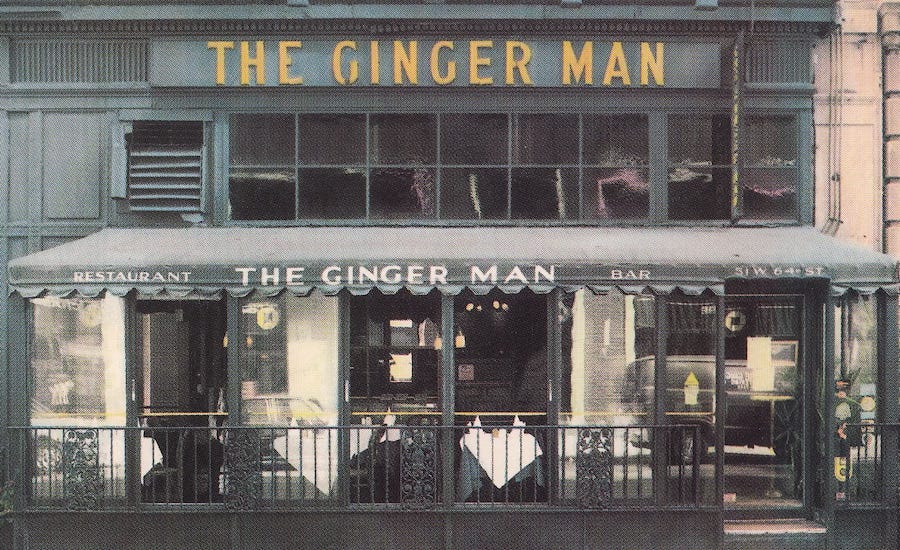

And yet despite the gap between the two, Griffin admires his brother—Oren riding a horse with mastery in the countryside; making $200 a night running food at a hot Columbus avenue restaurant as an 8th grader; stealing fancy driving gloves from one of their parents’ friends. He sums up their shared reality—a generational reality—here:

“The truth is that it would have never occurred to me then to share the things I’d seen and done, any more than discussing Kepplemen, because our lives were so atomized, because we lived so unattended, because we were already so strangely private, access to each other’s inner lives did not come naturally.”

In the second half of the book, with Shel and Lily’s marriage in question, Oren isn’t around, but his absences aren’t due to neglect on Ross’s part; it’s because Oren has a knack for self-preservation. He knows when not to be around.

Bad things happen in Playworld—like when the brothers get jumped, and Oren isn’t tough as much as he is a terrorized, frightened boy in tears—but Ross’s universe is not bleak or without hope. He doesn’t get off on torturing his characters. We see them at their worst but also at their best. Shel, whose vanity and failures embarrass his sons, gets his own chapter and it’s a good one.

And in one of the novel’s most touching sequences, Shel has a brief moment to shine in a short-lived Broadway production before it closes. He shows off his considerable gifts and Griffin beams watching his father.

I found myself cheering for them all, Shel, and Lily as they try and figure out their marriage—and themselves—during a divorce epidemic. Elliott the shrink. Naomi, too—about whom I haven’t mentioned much here simply to leave some mystery for those who haven’t read the book yet. Also family friend Al Moretti from Queens, and his crush Amanda’s mother, even Keppleman the wrestling coach—all the fucked-up grown-ups that populate this story.

But especially Griffin on his bicycle, as he moves inexorably into adulthood, eyes open, unattended, weaving through the crowd with a clarity that comes with calling your own shots.

Great book. Great review. Great photos. :-)

PHENOMENAL piece. Really brought the novel back to me - and enriched it.