Growing up, we visited my grandparents at their apartment on 15 West 81st street, between Columbus and Central Park West, almost every week. We’d usually be joined by aunt Biece and her husband Fred. He was taller than anyone in our family at 6’ 1, with sandy hair and a blond mustache, his Irish German countenance sharp relief to their Polish Russian stock or my mother’s Belgian blood.

Fred Garbers was as loud as any of them and just as opinionated but more childlike in how he expressed himself. He either “loooooved” something, as in, “How could you not love it?” Or he didn’t understand how you could like something he didn’t. He didn’t like Jackson Pollock (while crediting him with changing the path of art more than any of his peers). He didn’t understand Texas. He hated the Church and the Pope (the world’s biggest fascist), Republicans, Notre Dame University, the East Side of Manhattan, and, especially, his home borough Queens.

As kids, we sat on his lap and played with him. He made funny faces to us during the Passover Seder and sang the songs in a lovely baritone. A few years later, Fred would dip into the back room with us to check the score on the game, eyes glassy, smiling, invariably more interested in the game than the conversation in the living room with the grown-ups.

I liked my Uncle Fred because he was not my father. He had three kids of his own from a previous marriage, older than my sister, brother and me. Fred and my father had some business together, with Fred animating shorts for Sesame Street, but their joint projects didn’t come to fruition and the business went sour. After that, they co-existed uneasily and ragged on each other behind each other’s back.

Fred’s artwork, big canvases of rolling green hills in Ireland, dotted with sheep, or smaller Cape Cod sunsets, were on the walls of every family member’s home, and family friends, too, who were some of his most devoted patrons. The artwork was pictorial and inviting. So were some of his more quasi-surrealist still life’s, including a large canvas in my grandparents dining room. His presence was felt even when he wasn’t present.

Raised in South Ozone Park, Fred was the baby of his family and could draw from a young age. As a teenager, he took the subway to Manhattan by himself to listen to symphonies, watch the ballet, and visit art museums where he spent hours studying the masters. Kids in his neighborhood called him “Freddie the Artist” and the only reason he didn’t catch a beating is because he was also the quarterback of the local sandlot team and because his older brother taught him how to box.

He spent 32 months stationed in Alaska during the Korean War where he added Hank Williams and the military to his hate list. When he returned to New York he worked as a commercial artist, went to night school at Cooper Union, and spent his late nights drinking at the Cedar bar feet away from his Gods— Willem de Kooning and Franz Kline. He sometimes talked baseball with Kline, an Indians fan, at the bar and argued about art with his friends until the early hours of the morning.

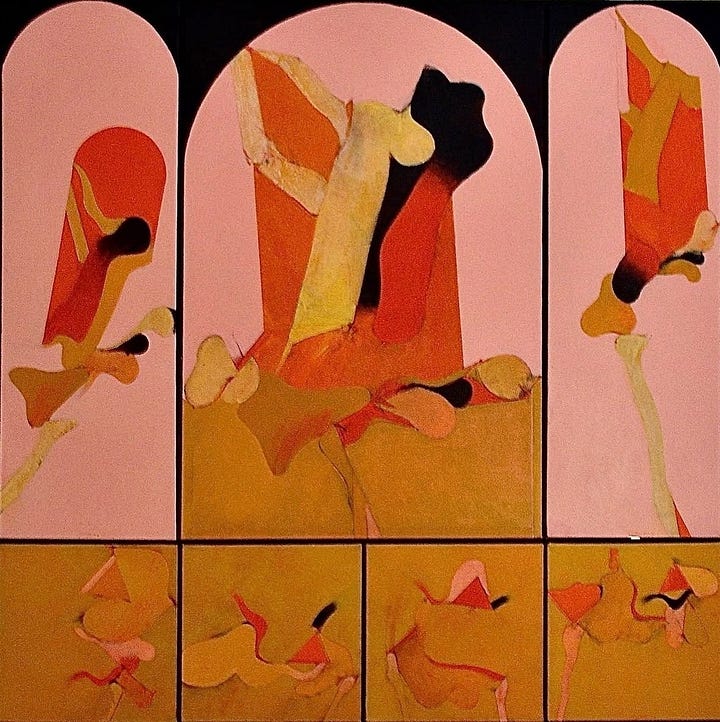

His career as a painter began in full abstract surrealist mode and he had pieces purchased by the Hirshhorn, The Addison Gallery of American Art, and the State University of New York, and had work appear in shows at the Modern, and the Whitney and the Albright Knox Gallery. Writing in the New York Times about Fred’s first solo show, Dore Ashton said, “This 28-year-old painter has a convincing dramatic sense and a commendable reserve.”

And so, Fred’s career ignited in a way he desired, represented by the Krasner Gallery from 1961-’79, where he averaged a one-man show every other year during the ’60s, and was featured in numerous group exhibitions.

But he had a family to support, three kids, a wife. They lived upstate and he continued to work as a commercial artist, taught drawing at a local college, and eventually turned to animation as a way to pay the bills. He created, drew, directed and did the voices for the cartoons (check out a mess of them, here). When my twin sister and I were three years old we did a voice over for one of his Sesame Street shorts.

Animation was a job; painting was his life. Fred came from the era where only fine artists were serious artists, or true artists. It’s a postwar romantic conceit—the one burst by Warhol and the Pop movement. Still, in Fred’s generation, illustrators, while gifted and able, were not in the same league as painters.

When I showed an ability to draw, Fred began pulling me aside at family gatherings in my grandparents’ apartment and got down on one knee like he was a quarterback in pickup football, drawing patterns in the dirt with a stick. He talked in a low voice about the integrity of drawing a still life—a bowl, a cup, an apple. A proud lapsed Catholic, Fred might have rejected the Church but spoke about art with religious reverence.

He took me to museums and delivered his own art history tour, especially at the Met, but also the Modern and Whitney, too. He and aunt Biece gave me my first art book—a paperback catalogue from an Edward Hopper show at the Whitney in 1981. I still have it.

Fred loved to look at things, deeply, in no hurry, a meditation. He was at ease in the country, having raised his kids in Rockland country. He knew how to build a fire from scratch, was an avid grill master, and was content to sit on a lawn chair and observe the flight paths of the local birds. Looking, for Fred, meant paying attention, being aware and alive without words.

He stood over my shoulder one summer morning next to a tool shed at a place in Connecticut my grandparents rented and guided me through drawing a light bulb hanging from a hook on the side of the shed.

He also had me over to his apartment a few times for art lessons, which I savored because they were a special occasion. My aunt and uncle lived in the same apartment my parents had lived in when my twin sister and I were born; we moved to a place on the other side of the building soon after, and Biece moved in. The floors creak, and it is an orderly, visually intriguing place. She’s still there to this day, where Fred’s art continues to adorn the walls.

I remember the first lesson because I slept over the night before. Biece was out with friends and Fred made the most delicious sandwiches with just a few thin slices of Genoa salami and Grey Poupon mustard on toasted English muffins. We savored them as we watched the Yankees game on TV. I was eight years old.

Our art lesson started early the next morning after breakfast. Fred made small pancakes with an almost crêpe-like consistency, each with a sliver of apple. He drank a large glass of milk, thought I was weird for not doing the same, and teased me for having a cup of tea instead.

After breakfast we went into the studio. I sat on the couch as he put a board on top of a stool in front of me, then placed a bowl and two bottles on the board. Fred took his time arranging them, then sat on the couch next to me, scrunching down to look at the still life from my eye level. Satisfied, he got up and brought me a pad of paper, a charcoal stick, and an eraser. He told me to really look at the objects as I draw them, not to press too hard or go too fast.

He also told me to pay attention to the space between the objects as much as the objects themselves.

I didn’t understand that.

I’d never used charcoal before and found it hard to control. The dark lines blurred when my hand brushed against the paper. Fred told me not to press so hard. I followed the outline of the cup with my eyes then looked at my paper and saw it didn’t look right. He sat next to me, scrunched back down, wiped off the paper, and redrew the top of the open cup. The marks he made looked unnatural at first, but once he completed the mouth of the cup, sure enough, it looked believable.

It seemed like a magic trick.

Fred told me to trust what I saw then left me for a while. I tried to synchronize my hand with my eyes. When my wrist began to ache, I stopped and folded the gummy eraser around in my hand like Silly Putty. I thought about last night’s Yankees game and those salami sandwiches, then looked back at the paper, discouraged.

I kept at it and I wouldn’t say the picture began to look good, but it became less bad. That’s when Fred came over and removed the cup from the still life. He replaced it with a candlestick.

“Now, you should be able to erase the cup from your picture and there should be a place for the candlestick,” he said.

I erased the cup and almost started crying. The two bottles looked like they were floating.

Fred sat next to me, put his arm around my shoulder, and laughed.

“Ha! All my students used to hate this assignment,” he said.

When you draw honestly, when your work means something, he said, it’s always a struggle.

Fred took the charcoal from me and drew the candlestick, adjusting and correcting the bottles until the drawing looked credible. I watched him looking from the objects to his paper and back, noticed where he made marks on the paper and the deliberateness of every move. I felt relieved that he was doing the work now.

When he was done he took away the candlestick. I erased it from the picture and the remaining objects were no longer rootless. I could see it, and suddenly understood that the empty or negative space was integral to connectedness, as important as the objects themselves.

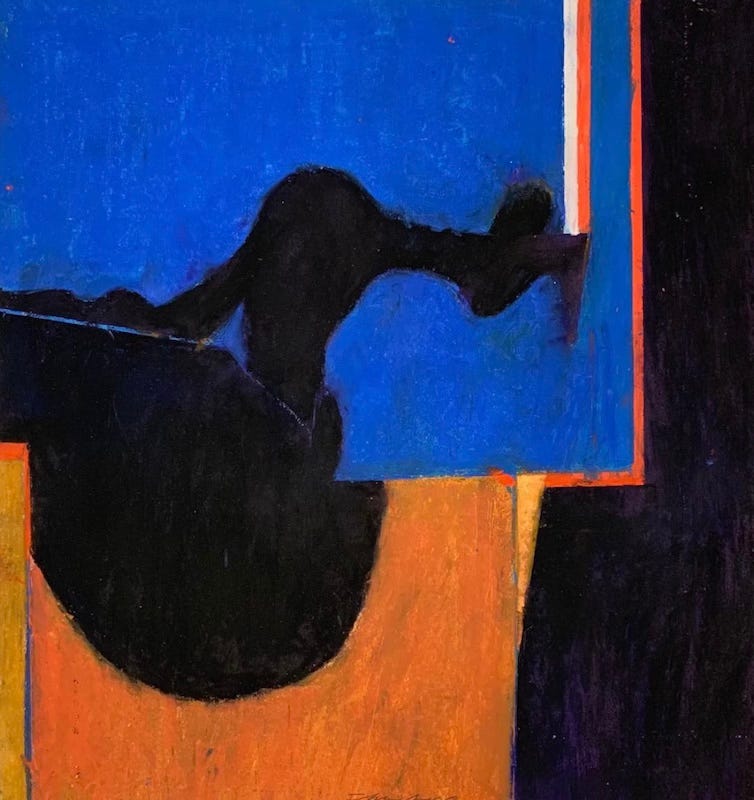

By the end of the ’80s, Fred grew bored making pretty landscapes and sunsets. He worked from his subconscious as naturally as any artist I’ve ever met, but I bet he was influenced by the show of Richard Diebenkorn’s drawings at the Modern in 1988. He gave me the monograph from the exhibition which came at a pivotal time as I struggled to understand abstract painting. Diebenkorn’s career could be broken down into three periods: abstraction, representation, and abstraction again. Looking through the book, you see the two idioms blur and overlap, making the differences between the two almost negligible. And, at least to me, comprehensible.

Here was Fred, returning to something he’d practiced years before but now, like Diebenkorn’s Ocean Park pictures, they had a distinct feel, and color palate of their own. He never painted representationally again.

Fred’s later work proved more challenging for viewrs because the audience, let alone market, for pure abstraction, is smaller than for representation. Fred continued to show in Manhattan galleries for the rest of his life, but he never made the kind of money some of his old pals did. And he didn’t have an ounce of the hustle in him. For someone who could be gregarious and engaging, selling himself was anathema to him.

Fred quit smoking, forever disgusted by anyone who didn’t do likewise. And like many drinkers of his generation, quit booze and shifted to wine. My father stopped drinking entirely and became a stalwart member of A.A., but he kept smoking off and on—mostly on—for the rest of his days—and Pall Malls too. He and Fred kvetched about each other, but they also found a way to accept or at least tolerate one another; beyond the hard feelings you could sense the bonds of brotherhood between them.

Fred didn’t understand my interest in comic books and graphic design or graffiti or why I wanted an airbrush. Through my teens and into my early twenties, I showed him my artwork, craving his approval. The tension between wanting it and wanting to be my own thing—and have his approval for that, too. But he liked what he liked and if he didn’t like something he wouldn’t lie about it.

On the other hand, when he liked something—and I always knew the pieces that he might dig—he swooned and encouraged.

But I wasn’t going to be a painter like him. I didn’t use my aptitude as a way to define myself. I always felt like I was letting him down when I took guitar lessons or was in the school play or read books and watched movies instead of drawing.

Still, it was something that kept us close. In the mid-’90s he even asked me to submit a painting to sit alongside one of his at a show on Cape Cod. I didn’t see it in person, but he sent a snapshot of him standing before my picture and I felt as if I’d arrived.

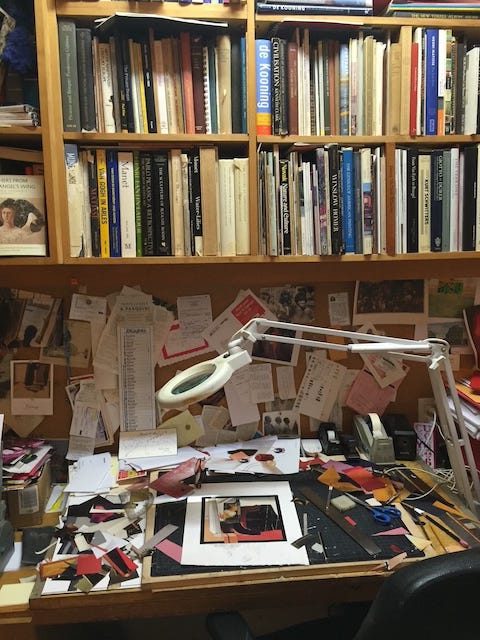

His body eventually betrayed him, though his creative powers did not, and he was still thinking about pictures until the end. The day before he died in 2017 he asked me to stretch a canvas for him. When he left us, an unfinished collage sat on the desk of his studio. Now, I can’t pick up a brush or a pencil or charcoal without that initial charge from his gentle calloused hand.

Fred’s late paintings might be abstract but are classical in their form, heavily influenced by Italian Renaissance altarpieces (oh, how he loved an annunciation). They’re active—the colors vibrant—and sensual, but also rigorous and controlled in a way that sometimes left me uneasy.

A few years before he died, I mentioned this to Fred, and he told me that he never thought about how his pictures made people feel.

“When an artist does something illogical,” he said, “they’re trying to make the viewer uncomfortable. And that’s a very nice thing to do. You’re on edge. Why am I on edge? Because the painter has taken the little harmony and put it out of balance so you’re a little out of balance, but it makes the picture interesting.”

I remember a landscape that hung in their living room long ago—my brother has it these days; the moon almost touching the top of a tree, an intentional decision that creates this curious tension for the viewer.

A couple of months ago, my aunt Biece was on vacation at the Cape, and I stayed at her place. At night, I stared at the patterns of light on the ceiling, these same walls that greeted me when I first came home from the hospital as an infant.

The longest home I’ve never known.

I watched a ballgame on TV in the den, his art studio where he gave me those lessons.

Since his death, I’ve left the city, and so have relatives and family friends. But alone in the apartment, I take comfort in how the old neighborhood feels the same, the pace, the faces, amidst the city’s relentless change.

I listen to the hum of late-night traffic on the West Side Highway, the clattering of garbage cans in a back alley. Are these the same sounds that were heard in this room more than 50 years ago?

I dream about my grandparents and my aunts and my uncles and my cousins, about my dad and Fred, all of them gone but still very much here in that space that we’ve created in-between. The space that is most important of all.

All images courtesy the family and estate of Fred Garbers.