Men Will Be Boys

Mike Tyson, R. Crumb, and Sam Shepard: Notes on American Manhood

When I went to college in the early ’90s, I hung around the acting kids in the theater department at college and quickly became acquainted with Sam Shepard: Seven Plays, a book that seemed to be on nightstands and make-shift bookshelves on and off campus. My friends chose Shepard for scene study class: True West for the boys; Fool for Love for a guy and a gal.

Inside those pages was a rock ’n’ roll poet in touch with a brand of American madness foreign to me. My heroes to that point were mostly urbane. But the image of Shepard on the worn paperback cover, along with a Fool For Love and Other Plays, where he almost smiles, proved hard to shake. It defined a kind of masculinity and cool that came from somewhere else, not just out west, but out in the country, apart, rural. I envied this chiseled brand of manhood which seemed to me unattainable; taciturn men made me anxious.

In Robert M. Dowling’s compelling new biography, Coyote: The Dramatic Lives of Sam Shepard, which I reviewed last weekend for The Wall Street Journal, we learn more about how he wrestled with what it meant to be a man. His father, a central figure in many of Shepard’s plays, was a World War II vet, and a violent alcoholic.

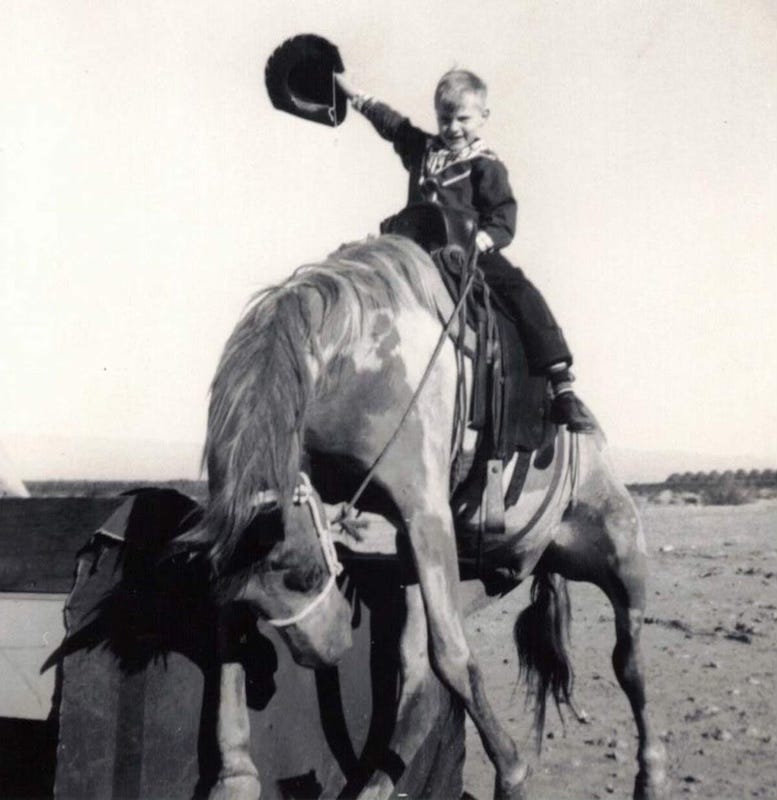

Shepard grew up just outside of Pasadena, California on a thee-acre, 65-tree avocado ranch. As a teenager, he gravitated to farm work, entering sheep into competitions, and caring for them—feeding, shearing, deworming, castrating. Before he graduated high school he worked at an Arabian horse ranch in Chino and those experiences invariably found their way into his writing.

According to Dowling:

In his darkly ironic short story “A Man’s Man,” the titular character is … based … at least in part on Shepard’s supervisor, called Duane in the story, whom he also considered “a man’s man.” The two of them raced against the Kentucky Derby winner Swaps in Duane’s Chevy, and Swaps won handily, to their delight. “I never heard of a horse beating a Chevy before, have you?” shouts Duane. “That’s gotta be a first!”

Once home in Bradbury, according to the story, Shepard awoke in Duane’s truck from a deep sleep after one of the most memorable days of his life, only to look down and find Duane’s hand resting on his privates. The appendage, Shepard wrote, “was just laying there limp, like a piece of raw hamburger. ‘You’re home,’ Duane said, and returned his hand to the steering wheel with a meek smile that made me suddenly sorry for him.” Shepard later confirmed that this was based on events he had experienced more than once. As late as 2010, while he was being interviewed for a documentary about him, these carnal abuses were still very much on his mind. “All these guys,” men he looked up to, blue-collar carpenters and painters and horsemen, would wind up with their hands on his crotch as a teenager. The way he saw it, they were treating him like his father had, “like a chick.”

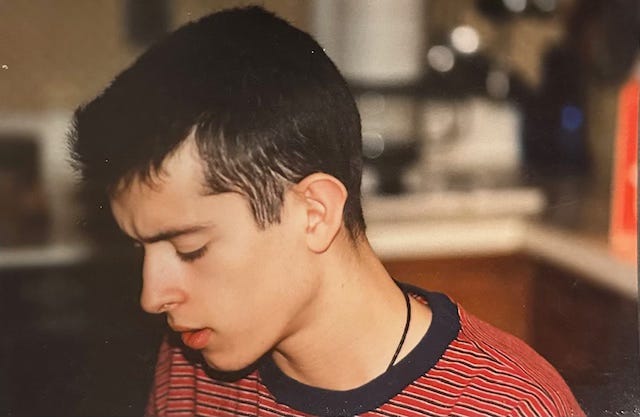

I often look back on my life as a young person and wonder how I avoided those situations. There was an incident with a doctor who worked at the clinic on my college campus; the guy touched me inappropriately, which didn’t register until I casually reported it to my therapist who said, “You were abused.”

I thought about this a good deal earlier this year when I read Adam Ross’s enchanting novel, Playworld. When I texted a childhood friend about it, he said that because I came from a good family—and a watchful one—I would never have been targeted by a predator. I don’t discount that, but my hunch is still that I got lucky. Because I remember how susceptible I was, desperate to be liked, and how easily I might have found myself in the wrong situation.

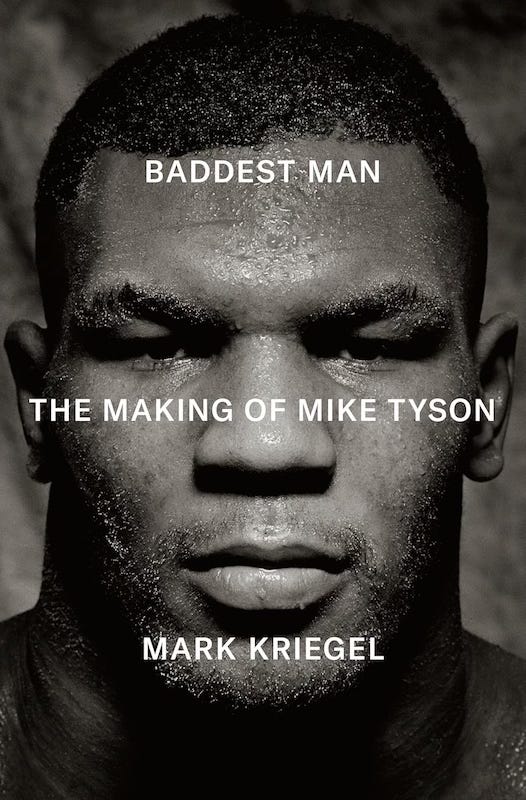

Mike Tyson wasn’t so fortunate. In Baddest Man: The Making of Mike Tyson, Mark Kriegel’s propulsive biography, we learn that at the age of seven, Tyson was molested by an older man, “and allowed that the experience was a seminal source of his rage.” Kriegel continues: “As for his attacker, he never saw him before or since. No idea who he was or where he came from. The Man—or perhaps the idea of him, of what or whom he represents—always appears in the same place, though. Symbolic or factual, I’m not sure. But it’s always an abandoned building.”

During my college years, nobody represented American manhood quite like Iron Mike, who, shortly into the second semester of my freshman year, unexpectedly lost the heavyweight title to a hump named Buster Douglas. Tyson seemed invincible until that night. The following year, he was arrested for rape and eventually sentenced to six years, of which he served three. Tyson didn’t fight again until 1995.

The guys I knew mocked his high voice, some disparaged his criminality, but beneath that, they revered him. Certainly, we feared him. After all, what was a more distilled version of manly power, than the fabled heavyweight champion of the world?

According to Kriegel:

Mike would do more than his share of smashing himself. He’d become a terror, which is to say that he trafficked in fear. The infliction of fear—the very panic it would arouse, the constricted breathing in a victim’s chest—would become Tyson’s most potent weapon, first on the street, then in the ring. But who has the most intimate knowledge of fear? Not the bully but what he had been; the vic, the. Bitch, the punk, the kid who’d been had. One didn’t become the Baddest Man on the Planet despite being traumatized but because of it.

“I always imagined that the people I was fighting were the people who had bullied me when I was younger,” he said.

Tyson, in many ways, was the last true heavyweight champ. Kriegel’s book only takes us through June of 1988, when Tyson, at 21, knocked out Michael Spinks in 91 seconds. Turns out that would be the peak of his professional career.

This is a story of talent and exploitation, of how people contort themselves around talent when money is on the table. And it is about the corrosive nature of fame. Kriegel, who covered the Tyson rape trial as a front-of-the-book columnist for the New York Post, long one of Tyson’s fiercest critics, turns out to be an ideal biographer, a skeptic who leaves us with a complicated but not unsympathetic portrait of Tyson.

Robert Crumb was familiar with being an outsider, his family’s eccentricities and traumas having been immortalized in Terry Zwigoff’s 1994 documentary, Crumb—much to the artist’s mortification. Like Shepard, his father was a military man (Marines) and could not understand his artistic-minded sons. Crumb is also the subject of an excellent biography this year—Crumb: A Cartoonist’s Life—by comic book historian and curator, Dan Nadel. If Dowling and Kriegel faced the challenge of not talking to their subject or their inner circles, Nadel is challenged by having full access to Crumb and his considerable archive.

Fortunately for him, Crumb not only kept revealing journals, but he’s candid, introspective and unapologetic in interviews. Nadel makes the most of this access without getting overwhelmed, and maintains a steady, detached critical eye throughout.

I always wished I had an older sibling to hip me to the ways of the world. Crumb was one of those guys—like Lenny Bruce—you learned about from an older, cool kid. My college pal Jay Bird had an older brother, Richie, who introduced him to Crumb as well as Shepard—that’s how I came to Crumb, through a big brother once removed.

I’d grown up going to comic book conventions at the Roosevelt Hotel, reading Franco-Belgian comic books (Bandes dessinées) from my mom’s family in Belgium, and only knew a little about underground comics beyond Cerebus. I was familiar with Keep on Truckin’ and the Janis Joplin album cover and Fritz, of course, but when I first looked at Crumb’s comics I felt as if I’d already ingested him, unknowingly, like secondhand smoke.

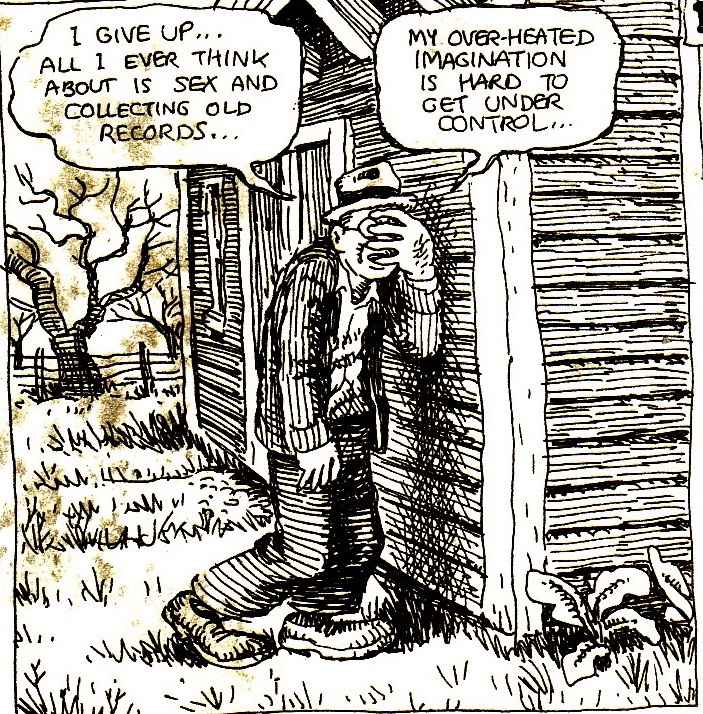

His pictures about sex got my attention, for sure, but how he operated from a deep place, close to the unconscious, was even more liberating. I admired his craftsmanship—awed and sometimes put-off by it, too. His discipline and productivity were resolute, as were his self-loathing and rage, which I found easier to identify with than Shepard’s; I may have been shocked by Crumb’s work but it wasn’t alien to me.

Like Shepard, Crumb possessed huge ambition. In a 1961 letter to a friend, Crumb wrote:

“A greatness complex can certainly be a hindrance when one is trying to look reality in the face…It always gets in the way. How can I be sincere in my work if subconsciously I’m only concerned with living up to the standards of greatness? I hope I can get rid of this drive for fame…It’s false and stands in the way of knowing myself…I don’t think it hurts a person to take out a few months, if they are fortunate enough to get the opportunity to dream and think about things. So many people go through life never really knowing who they are or what they want. Because they think it’s wrong if they are not constantly accomplishing something…constantly achieving things…my father is that way…life to him is how much you can do and how good you are at it…the only way you can reach self-understanding is by getting away from it all…work, even books…You have to withdraw into yourself as much as possible, and concentrate only on getting at truth.”

It seems incongruous to look at ambition as a hinderance. I love that Crumb is saying to be original there is a time of Not Doing. Of withdrawing. Like that moment in Hemingway’s story “A Short Happy Life,” where Frances Macomber talks about “going into the mountains and cutting away all the fat from his soul the way a fighter goes into the mountains to train.” Crumb had massive ambition, but the thing he’s saying that’s really interesting is how to cut past fame into the truth.

What is that place for artists like Shepard and Crumb? How does that space represent trauma for a boxer like Tyson and is not replicable in regular civilian life?

Shepard courted fame and also loathed it. He understood how it interfered with his writing, his longest lasting obsession. He’s far cagier than Crumb, who, like George Carlin, has a wonderful capacity to articulate himself and speak honestly. Shepard and Crumb both lived peripatetic lives, full of searching, and obsessions—chiefly, their work.

How did their work survive their ambition?

Here’s more from Crumb:

“You often read about artists, musicians who, as they get older, they get less spontaneous and just more involved in technique. That happened to me. It did. I’m a typical case of that. Losing the playfulness, that’s the danger. Happens to musicians. A lot of the jazz musicians I admire became technically better later. But in their early stuff, though they’re not as technically proficient, it has the bright enthusiasm of youth. And it’s also more social. Later they withdraw into their technical challenges, as life will do to anyone in any art form.”

It’s not easy for artists to cut through the false smoke of fame into a place that is true artistically—and that place is like play. I’m reminded of that choice Joyce Carol Oates quote from On Boxing where she separates it from all other sports and says that one does not “play at boxing.” Its stakes are all different. The moral seriousness. Maybe that is why we love Tyson, warts and all, now because he gets to be in The Hangover and dumb reality shows and be a regular civilian. We see him at play.

As a reader, it’s a privilege to take stock of a person’s life, to learn what they did and who they knew, and what they left behind. When I was younger and read biographies I ranked people’s lives based on their accomplishments. Now, I’m curious about how they lived, what kind of happiness they achieved—if that was even a possibility—as much as what they created. And this: Was work enough?

We often hear that men are defined by what we do. Work gives us purpose and meaning and helps feed our families. What happens when that’s over? Who are we beyond work?

Two years before he died, Shepard asked himself in a journal entry: “What are you going to do now that you’ve done everything you’ve wanted?”

Indeed. What’s next? What’s tomorrow? And before that—what’s right now, this very moment?

I love biographies and have read them regularly since my teens, mostly about artists and filmmakers and athletes and writers. Been a mess of intriguing ones this year; here’s a list of biographies from 2025 that I’ve enjoyed and am making my way through:

Mark Twain by Ron Chernow

The Colonel and the King by Peter Guralnick

Wild Thing: A Life of Paul Gaugin by Sue Prideaux

Joan Crawford: A Woman’s Face by Scott Eyman

Baldwin: A Love Story by Nicholas Boggs

Desi Arnaz by Todd S. Purdum

Yoko by David Shelf

Buckley by Sam Tanenhaus

Lorne by Susan Morrison

The Pilgrimage of Peter Matthiessen by Lance Richardson

Woody Allen: A Travesty of a Mockery of a Sham by Patrick McGilligan

Dark Renaissance: The Dangerous Times and Fatal Genius of Shakespeare’s Greatest Rival by Stephen Greenblatt

Peace is a Shy Thing: The Life and Art of Tim O’Brien by Alex Vernon

Cool than Cool: The Life and Work of Elmore Leonard by C.M. Kushins

There are tasty-looking volumes I haven’t gotten to yet, including the Amelia Earhart book and Toni at Random by Dana A. Williams, or new ones on Denis Johnson and John Prine.

I adored When Caesar Was King by David Margolick—which I have already written about, I just loved it. Currently, I’m in the middle of Trouble Maker: The Fierce, Unruly Life of Jessica Mitford by Carla Kaplan, so thoroughly enjoying myself I’ve started reading it slower because I don’t want to rush, and don’t want it to end.

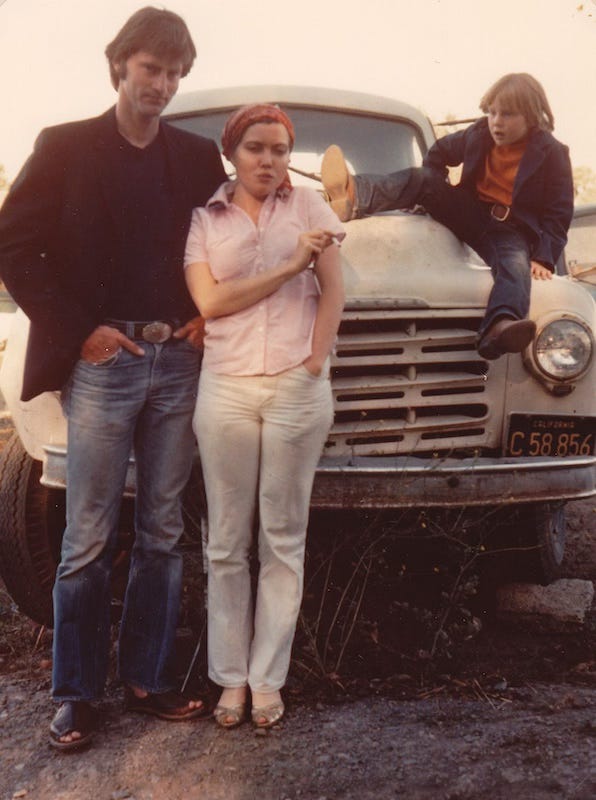

[Photo Credits from Coyote, published by Scribner: Shepard as a child, courtesy Grace Upton; Shepard and family, courtesy the Sam Shepard & Johnny Dark Collections, The Witliff Collections, Texas State University; Douglas Kent Hall/Princeton University Library.]

This is unexpectedly great and accidentally micro-targeted at me. So thank you!! I didn't want to read it. I get way too much stuff in my inbox and am in a mood to just think my own thoughts this week. Worse, these three never really had much of an impact on me personally. But something in your way of relating these very "other" lives to your own kept me reading -- and then you just took it to a most profound cage-rattle about work, ambition and time. I'll be saving this one and reading it again. For the questions. Good questions. Thanks.

Wow. Even factoring out, or trying to, my own self-interest, this is really well done. Thank you, Alex.